India is the leading source of shrimp found by FDA to be contaminated with either salmonella or banned antibiotics

In August 2013, the U.S. Department of Commerce issued a final determination finding that the Indian government provided significant countervailable subsidies to Indian shrimp producers and exporters.[1]

Unfortunately, the U.S. government has taken no action to countervail those subsidies since Commerce announced that finding.

In the intervening five years, support from the Indian government to its shrimp industry has only increased as part of that government’s initiative to rapidly expand shrimp aquaculture. Those efforts have been incredibly successful, leading to Indian shrimp flooding the world market. In 2010, the United States imported just under $300 million worth of non-breaded frozen warmwater shrimp from India. Last year, that amount had grown seven-fold, with the United States importing $2.2 billion worth of these Indian shrimp. That explosion has led India to become the most significant supplier of imported shrimp into the U.S. market. Last year, India accounted for 35 percent of the volume of all U.S. imports of non-breaded frozen warmwater shrimp, up from 6 percent in 2010.

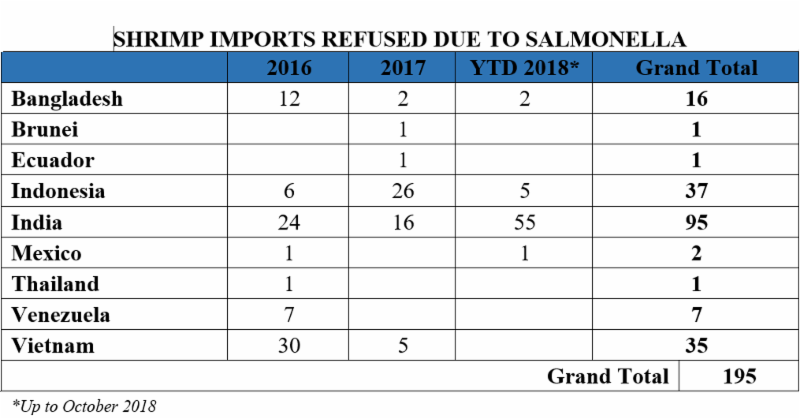

Why is this such a pressing issue? The influx of Indian shrimp in the U.S. market causes several health and safety concerns. Within the past few years alone, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has reported an absurdly high number of refusals of shrimp imports from India containing traces of salmonella, in comparison to shrimp imports from other countries. From 2016 through August 2018, India accounted for 33 percent of the volume of all non-breaded frozen warmwater shrimp imports into the United States. Yet, at the same time, as shown in the table below between 2016 and October 2018, India has accounted for 49 percent of the entry lines of shrimp refused by the FDA for the presence of salmonella:

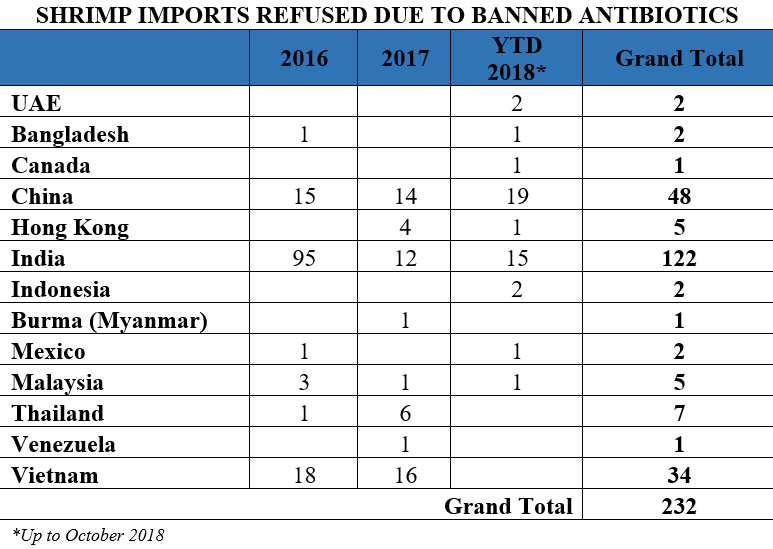

Similarly, from 2016 through October 2018, shrimp from India accounts for 52 percent of the entry lines of shrimp refused by the FDA for reasons related to banned antibiotics.

India supplies nearly one-third of the shrimp available in the United States and about half of the shrimp imports found by FDA to be contaminated with either salmonella or banned antibiotics. The FDA’s continued and repeated detection of salmonella or banned antibiotics in Indian shrimp raises important questions regarding the development and spread of antimicrobial resistant (AMR) pathogens in Indian aquaculture and the possibility that Indian shrimp imports may act as a vehicle for the introduction of AMR bacteria into the United States.

Separate and apart from the efforts from the FDA to regulate contaminated Indian shrimp, the European Commission has recently emphasized its concerns regarding Indian shrimp aquaculture. The European Commission conducted an audit on Indian aquaculture in April 2018. The audit focused on the control of antibiotics in all aquaculture, but focused especially on shrimp farming.

In response to the results of the audit, the European Commission explained that although member countries currently tested for chloramphenicol, tetracycline, oxytetracycline, chloratetracycline and nitrofurans, member countries were advised to consider also expanding the scope of their testing to also encompass cephalosporins, lincosamides, diaminopyrimidies, and doxycycline.

These four types of antibiotics are generally not included in the classes of antibiotics that are tested for by regulatory authorities in major seafood importing countries. However, each of these classes of antibiotics has important therapeutic applications that are endangered by the development and emergence of AMR bacteria. A short description of each of these four classes of antibiotics is set out below.

CEPHALOSPORINS

Cephalosporins are a group of antibiotics that belong to the “beta-lactams” class and are similar to penicillin. They are used to cure various infections such as respiratory tract infections, skin infections and urinary tract infections. Studies show that bloodstream infections caused by E. coli are resistant to third-generation cephalosporins.[2]

In January 2012, the FDA issued an order that prohibited certain uses of cephalosporin in food-producing animals.[3] The FDA explained its efforts to reduce the use of cephalosporins in livestock rearing because:

The cephalosporin class of drugs is important in treating human diseases, such as pneumonia, skin and tissue infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, and other conditions. It is critical to preserve the effectiveness of these drugs.

FDA is concerned that certain extralabel uses of cephalosporins in cattle, swine, chickens and turkeys are likely to contribute to cephalosporin-resistant strains of certain bacterial pathogens. If cephalosporins are not effective in treating human diseases from these pathogens, doctors may have to use drugs that are not as effective or that have greater side effects.

The Agency is particularly concerned about the extralabel use of cephalosporin drugs that are not approved for use in cattle, swine, chickens and turkeys because little is known about their microbiological or toxicological effects when used in these food-producing animals.[4]

DOXYCYCLINE

Doxycycline is commonly used to treat various respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia and bronchitis.[5] It also used to treat acne and urinary and genital infections.

Doxycycline can also be used as a preventive measure against malaria for tourists and military personnel traveling to tropical countries.[6]

In terms of veterinary use, doxycycline is administered to animals intravenously or orally to treat bacterial infections and tick-borne diseases.[7]

The Canadian Government includes doxycycline in its “Aquaculture Therapeutant Residue Monitoring List,” and notes that it is “not accepted to be used.”[8]

LINCOSAMIDES

Lincosamides are a family of antibiotics composed of lincomycin and clindamycin, and are particularly helpful for treating bone and joint infections.[9]

For veterinary use, lincosamides are generally used to treat gram-positive bacterial infections in companion animals.[10]

DIAMINOPYRIMIDINES

Also known as amifampridine, diaminopyridine (DAP) is widely known for its effectiveness in treating neuromuscular disorders.[11]

It is unclear whether or not certain bacteria has developed resistance to DAP yet.

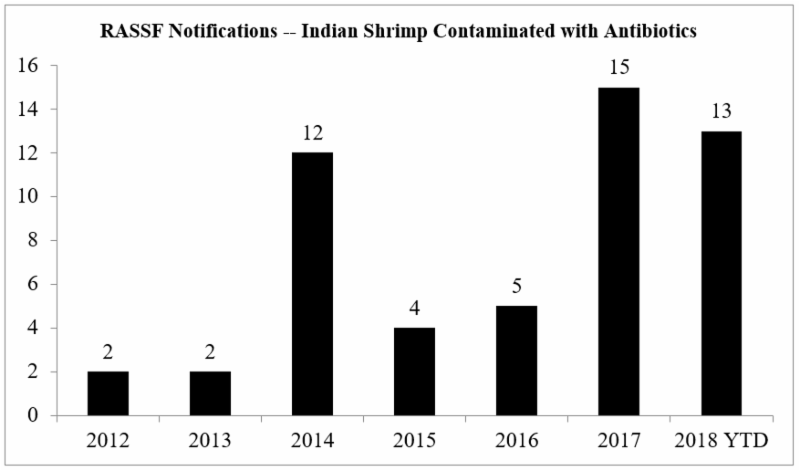

The European Commission’s advice to member countries to expand their testing regimen comes at a time of a significant increase in the number of the notifications provided through the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) for the presence of banned antibiotics in Indian shrimp imported into the European Union.

The chart below summarizes the annual number of RASFF notifications issued regarding antibiotics found in Indian shrimp between 2012 and October 2018:

And, yet, this increase in RASSF notifications is occurring simultaneous with a sharp decline in Indian shrimp exports to the European Union. Member countries of the European Union were, collectively, historically the main purchasers of Indian seafood products, accounting for a substantial portion of India’s exports. However, stricter enforcement by the European Commission has led the export share volume to the European Union to reportedly decrease from 33 percent to 16 percent of all Indian exports.[12] Indian shrimp exporters have more than compensated for this decline in shipments to the European Union by re-directing shipments to the United States.[13]

Footnotes:

[1] Certain Frozen Warmwater Shrimp from India, 78 Fed. Reg. 50,385 (Dep’t Commerce, Aug. 19, 2013) (Final Affirmative Countervailing Duty Determination).

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.